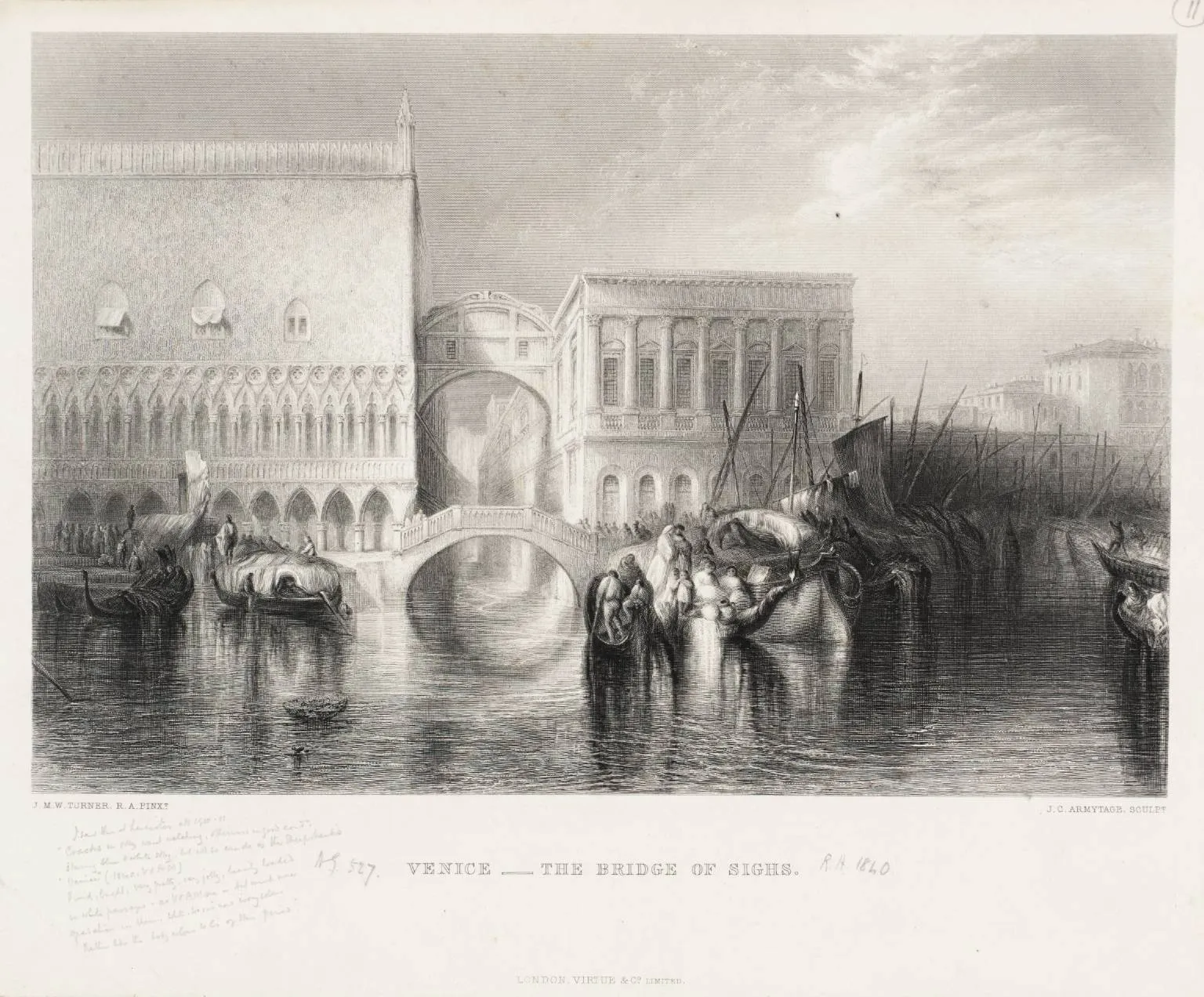

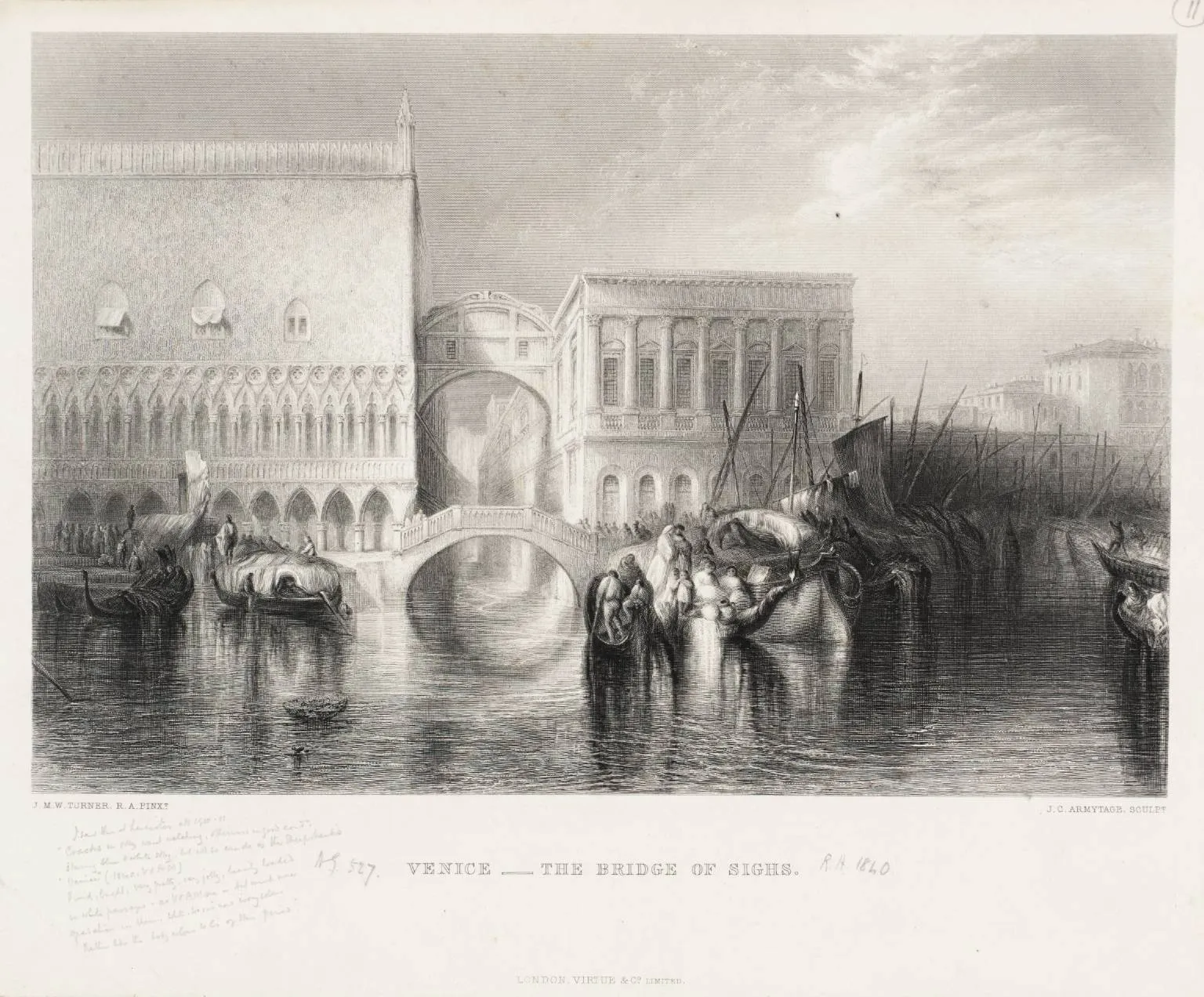

An enclosed arch above a quiet canal

Discover how Venice shaped a delicate bridge of stone — where footsteps echoed, windows filtered the light, and the city watched in silence.

Table of Contents

Origins: palace, prisons, and a bridge

In the early 17th century, Venice linked two worlds across the Rio di Palazzo: the ornate Doge’s Palace, where councils debated and magistrates judged, and the New Prisons, where sentences were served. The Bridge of Sighs was the discreet corridor between them — neither grand entrance nor dramatic exit, but a narrow passage of workaday justice.

Its name, ‘dei Sospiri,’ invites stories. Some say prisoners sighed at their last view of daylight through the small latticed windows. Others think of families waiting outside, or the city itself, exhaling as affairs of law wound down for the day. Whatever the origin, the bridge gathers Venice’s habit of poetry around practical stone.

Design and construction in stone

Crafted in Istrian limestone, the Bridge of Sighs follows a gentle arch across the canal. Antonio Contino, the architect, shaped a compact, enclosed span with ornamental reliefs at its base and delicate window lattices that sift the light. The result is restrained Baroque: elegant rather than flamboyant, attentive to purpose as much as to beauty.

Inside, the corridor is simple: stone underfoot, narrow walls, a hush that carries footsteps forward. Yet even here, detail matters — the rhythm of windows, the turn toward the prisons, the way the bridge frames glimpses of water and sky. Venice often hides its craft in small places; the Bridge of Sighs is one of them.

Windows, lattices, and filtered light

From outside, the bridge’s openings look like intricate tracery. From inside, they soften the world beyond: faces at the quay become silhouettes, ripples on the canal turn to moving lines of silver, and the city’s sound becomes a distant murmur. The bridge is both threshold and filter — a pause between rooms, a breath between roles.

Over time, the windows gathered wear: touch‑polished stone, small chips, and the patina of thousands of days. The view remains the same and always different — a brief rectangle of Venice that travelers and Venetians have shared in passing.

Justice, footsteps, and the meaning of ‘sighs’

The bridge’s daily life was work: magistrates finishing hearings, scribes closing ledgers, guards guiding prisoners. Footsteps crossed with routine gravity. If there were sighs, they belonged to many — officials, witnesses, and those whose paths turned toward the cells. Venice handled law as a civic ritual; the bridge kept the ritual moving, quietly.

Romance later found the bridge and gave it a different script: lovers kiss beneath on a gondola at sunset, the story goes, and time grants them luck. The myth sits nicely on the stone, but its true drama is gentler — a city accepting its work, a canal carrying its reflections, and travelers finding meaning in a single brief arch.

Graffiti, memory, and small traces

The prisons beyond the bridge hold marks of time: faint inscriptions, scratched names, the geometry of bars and locks. These are small records rather than grand statements — fragments of presence that remind us the city’s story is both official and personal.

Guides sometimes pause by these walls, letting silence do its work. In Venice, memory often arrives sideways: a corner, a window, a corridor that keeps secrets in plain sight.

Ceremonies, pardons, and city ritual

Venice organized law with ceremony: appointments, councils, and a cadence that shaped the city’s rhythm. Pardons were granted, sentences recorded, and appeals prepared with the formality of a maritime republic. The Bridge of Sighs carried these routines like a small artery — unnoticed until you look.

Standing outside, you might watch the bridge as part of a larger scene: the Doge’s Palace, the quays, the lagoon’s wind. It’s a civic landscape where each element plays a part — even the modest ones.

The Rio di Palazzo and Venice’s stage

The canal below is narrow and theatrical. Gondolas slide under the arch, crowds gather along the balustrades, and cameras rise as boats drift into the rectangle of stone. The moment is brief and oddly peaceful — a vignette of Venice that feels scripted and spontaneous all at once.

Walk to both viewpoints — one facing the lagoon, one inside the city — and notice how the light changes. In the morning, the stone glows cool; at sunset, it warms with a quiet rose. Small bridges teach patience.

Acqua alta, maintenance, and accessibility

During acqua alta (high water), raised walkways may line the quays, changing foot traffic and views. Schedules can shift for safety, and palace routes may adjust. The bridge itself endures — a patient witness to tides and time.

Accessibility is mixed: exterior viewpoints are step‑free; interior passages include thresholds and stairs. Staff help where possible, and updated routes continue to improve access.

Art, literature, and cultural echoes

Writers and painters found the Bridge of Sighs irresistible — a compact symbol that can carry romance, justice, melancholy, or humor depending on the day. Byron gave it fame; visitors give it continuity.

Exhibitions, restorations, and careful stewardship keep the bridge legible: neither over‑polished nor left to fade, a piece of Venice maintained with respect.

Visiting today: tickets and timings

Book Doge’s Palace entries with prisons access to cross the Bridge of Sighs inside. Timed slots help keep your day unhurried.

For exterior views, arrive early or linger later. If you’d like the gondola angle, pick quieter hours when the canal feels more like a stage than a queue.

Conservation, respect, and sustainability

Conservators monitor stone, joints, and surfaces, balancing cleaning with patina. Your respectful visit — patient, careful, and curious — helps keep the bridge’s surroundings calm.

Choose off‑peak times, follow staff guidance, and remember that Venice is both delicate and resilient. Small acts accumulate like tides.

Nearby sights: palace, quays, and gondolas

Steps away, the Doge’s Palace opens into courtyards and grand rooms; the waterfront leads to views over St. Mark’s Basin and the island of San Giorgio Maggiore.

Take time to watch gondolas, listen to the water, and notice how the light edits the scene — Venice is a patient storyteller.

Why the Bridge of Sighs matters

It’s small, but it’s telling: a bridge that carried daily law, gathered myths without asking, and became a gentle emblem of Venice’s way of turning work into poetry.

A visit connects you to the city’s quieter rhythm — footsteps in a corridor, ripples under an arch, and the feeling that history here is close enough to hear.

Table of Contents

Origins: palace, prisons, and a bridge

In the early 17th century, Venice linked two worlds across the Rio di Palazzo: the ornate Doge’s Palace, where councils debated and magistrates judged, and the New Prisons, where sentences were served. The Bridge of Sighs was the discreet corridor between them — neither grand entrance nor dramatic exit, but a narrow passage of workaday justice.

Its name, ‘dei Sospiri,’ invites stories. Some say prisoners sighed at their last view of daylight through the small latticed windows. Others think of families waiting outside, or the city itself, exhaling as affairs of law wound down for the day. Whatever the origin, the bridge gathers Venice’s habit of poetry around practical stone.

Design and construction in stone

Crafted in Istrian limestone, the Bridge of Sighs follows a gentle arch across the canal. Antonio Contino, the architect, shaped a compact, enclosed span with ornamental reliefs at its base and delicate window lattices that sift the light. The result is restrained Baroque: elegant rather than flamboyant, attentive to purpose as much as to beauty.

Inside, the corridor is simple: stone underfoot, narrow walls, a hush that carries footsteps forward. Yet even here, detail matters — the rhythm of windows, the turn toward the prisons, the way the bridge frames glimpses of water and sky. Venice often hides its craft in small places; the Bridge of Sighs is one of them.

Windows, lattices, and filtered light

From outside, the bridge’s openings look like intricate tracery. From inside, they soften the world beyond: faces at the quay become silhouettes, ripples on the canal turn to moving lines of silver, and the city’s sound becomes a distant murmur. The bridge is both threshold and filter — a pause between rooms, a breath between roles.

Over time, the windows gathered wear: touch‑polished stone, small chips, and the patina of thousands of days. The view remains the same and always different — a brief rectangle of Venice that travelers and Venetians have shared in passing.

Justice, footsteps, and the meaning of ‘sighs’

The bridge’s daily life was work: magistrates finishing hearings, scribes closing ledgers, guards guiding prisoners. Footsteps crossed with routine gravity. If there were sighs, they belonged to many — officials, witnesses, and those whose paths turned toward the cells. Venice handled law as a civic ritual; the bridge kept the ritual moving, quietly.

Romance later found the bridge and gave it a different script: lovers kiss beneath on a gondola at sunset, the story goes, and time grants them luck. The myth sits nicely on the stone, but its true drama is gentler — a city accepting its work, a canal carrying its reflections, and travelers finding meaning in a single brief arch.

Graffiti, memory, and small traces

The prisons beyond the bridge hold marks of time: faint inscriptions, scratched names, the geometry of bars and locks. These are small records rather than grand statements — fragments of presence that remind us the city’s story is both official and personal.

Guides sometimes pause by these walls, letting silence do its work. In Venice, memory often arrives sideways: a corner, a window, a corridor that keeps secrets in plain sight.

Ceremonies, pardons, and city ritual

Venice organized law with ceremony: appointments, councils, and a cadence that shaped the city’s rhythm. Pardons were granted, sentences recorded, and appeals prepared with the formality of a maritime republic. The Bridge of Sighs carried these routines like a small artery — unnoticed until you look.

Standing outside, you might watch the bridge as part of a larger scene: the Doge’s Palace, the quays, the lagoon’s wind. It’s a civic landscape where each element plays a part — even the modest ones.

The Rio di Palazzo and Venice’s stage

The canal below is narrow and theatrical. Gondolas slide under the arch, crowds gather along the balustrades, and cameras rise as boats drift into the rectangle of stone. The moment is brief and oddly peaceful — a vignette of Venice that feels scripted and spontaneous all at once.

Walk to both viewpoints — one facing the lagoon, one inside the city — and notice how the light changes. In the morning, the stone glows cool; at sunset, it warms with a quiet rose. Small bridges teach patience.

Acqua alta, maintenance, and accessibility

During acqua alta (high water), raised walkways may line the quays, changing foot traffic and views. Schedules can shift for safety, and palace routes may adjust. The bridge itself endures — a patient witness to tides and time.

Accessibility is mixed: exterior viewpoints are step‑free; interior passages include thresholds and stairs. Staff help where possible, and updated routes continue to improve access.

Art, literature, and cultural echoes

Writers and painters found the Bridge of Sighs irresistible — a compact symbol that can carry romance, justice, melancholy, or humor depending on the day. Byron gave it fame; visitors give it continuity.

Exhibitions, restorations, and careful stewardship keep the bridge legible: neither over‑polished nor left to fade, a piece of Venice maintained with respect.

Visiting today: tickets and timings

Book Doge’s Palace entries with prisons access to cross the Bridge of Sighs inside. Timed slots help keep your day unhurried.

For exterior views, arrive early or linger later. If you’d like the gondola angle, pick quieter hours when the canal feels more like a stage than a queue.

Conservation, respect, and sustainability

Conservators monitor stone, joints, and surfaces, balancing cleaning with patina. Your respectful visit — patient, careful, and curious — helps keep the bridge’s surroundings calm.

Choose off‑peak times, follow staff guidance, and remember that Venice is both delicate and resilient. Small acts accumulate like tides.

Nearby sights: palace, quays, and gondolas

Steps away, the Doge’s Palace opens into courtyards and grand rooms; the waterfront leads to views over St. Mark’s Basin and the island of San Giorgio Maggiore.

Take time to watch gondolas, listen to the water, and notice how the light edits the scene — Venice is a patient storyteller.

Why the Bridge of Sighs matters

It’s small, but it’s telling: a bridge that carried daily law, gathered myths without asking, and became a gentle emblem of Venice’s way of turning work into poetry.

A visit connects you to the city’s quieter rhythm — footsteps in a corridor, ripples under an arch, and the feeling that history here is close enough to hear.